Compassion and Empathy are Providers’ Superpowers

Author

South Shore Health

When he came to visit his critically ill friend and colleague in the hospital, Allen Smith, MD, MS had three wishes for Dr. Michael Hession.

First was that he would survive; second, he would write a book about his near-death experience and recovery; and third, he would share his inspirational story with other healthcare providers.

All three wishes came true.

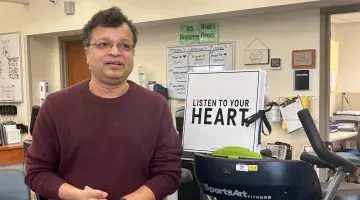

With his wife Colleen by his side, and his recently published book “Physician Heal Thyself” in hand, Hession captivated a standing-room-only Schwartz Rounds, recounting the critical illness that nearly took his life, his long and winding journey back to health, and the invaluable lessons he learned as a patient and as a physician.

Hession’s message about the power of empathy and compassion when caring for patients was an apt one for Schwartz Rounds – a forum that brings healthcare staff together regularly to reflect on the emotional aspects, rewards and challenges of patient care.

Named in honor of Ken Schwartz, founder of the Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare, Schwartz Rounds offers a safe space for caregivers to open up about their personal experiences and the connections they make with patients.

Those caregiver-patient connections were particularly meaningful to Schwartz, a healthcare attorney who battled advanced lung cancer at just 40 years old. The compassionate care he received while undergoing treatment inspired Schwartz to create an organization that would foster and support compassion and humanity in healthcare.

Hession came to know first-hand, “the smallest acts of kindness” that Schwartz described in his Boston Globe Magazine article, “A Patient’s Story,” do indeed, make the “unbearable bearable.”

The start of a cold, and nearly the end

What began as cold symptoms in the weeks before Christmas 2013, devolved into a dangerous pneumonia – acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) by New Year’s Eve, leaving Hession laboring to breathe.

As a cardiologist, Hession knew pneumonia could be a serious health risk and took it seriously. He had seen his provider, was taking antibiotics and managing the illness, when Colleen said, “he just dropped off a cliff.”

“I was watching him sleep and could tell he was really struggling for every breath,” she said. “I knew as a nurse myself with years of ICU experience, this could not be sustained.”

Colleen called 911, and Hession was taken by ambulance to South Shore Hospital – where he has been on staff since 1985.

Familiar faces filled with concern relayed difficult news about Hession’s deteriorating condition.

Hession’s breathing was not improving on the BiPAP machine in the Emergency Department and he was moved to the CCU where he was intubated and put on life support.

“Everything was moving so quickly, it was a blur,” said Colleen, who was told efforts to oxygenate her husband were not working and he needed to be transferred to Brigham and Women’s Hospital where ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), an artificial lung for patients failing on mechanical ventilation, was available.

“They made quick decisions and did everything they could possibly do,” Hession said of the South Shore Hospital staff that saved his life that night.

Family matters, and words are powerful

His battle was far from over, however. Hession spent 13 days at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 11 of them in the ICU – intubated, sedated and unable to move or speak.

Colleen was his voice and advocate, and was by his side nearly constantly. When she was not, other family members – including sons, Michael and Patrick and Hession’s siblings, stepped in.

“No one knows Michael better than I do,” said Colleen, who shifted into “nurse mode” with Hession’s hospitalization.

By staying in nurse mode, Colleen said she was able to keep her family informed and “cope with the severity of what was going on.”

As a nurse, Colleen had the advantage of understanding all the medical terminology and keeping up with Hession’s test results, treatments and condition, which she could relay to him, and their family and friends.

While he was intubated and unable to move or speak, Hession was able to hear, and said hearing Colleen and other family members’ voices speaking to him, was tremendously comforting during a terrifying time.

Hession said he was thankful for the caregivers who took the time to explain a procedure before doing it or simply spoke to him empathetically.

“Words are powerful and speaking with your patients with empathy and compassion, however briefly, goes a long way toward allaying their fears and acknowledging their humanity,” he said.

Hession recounted a story of one of his nurses who started each shift by speaking into his right ear, telling him her name, the time, date, day and what was planned for the day.

“This one-way conversation took no more than a minute, but I was so appreciative of the compassion and empathy she showed me,” Hession said.

“The power of this act – treating me as a sentient human being and not as a piece of furniture, still resonates with me today.”

The darkness, the light and the woman in the luminous robe

During his days intubated in the ICU, Hession required suctioning treatments to clear his airway. Hession writes about the painful, invasive procedure in his book, including the instance that preceded a near-death experience.

“After another suctioning treatment, things again went dark,” Hession wrote. “This time, I don’t recall waking the way I did after the prior treatments.”

Amid the darkness, Hession describes hearing the mournful sound of keening – the Gaelic word for the wailing that comes following the death of a loved one. He recounts feeling cold inside, the warmth leaving his body, and the sensation of floating in the darkness, away from the keening of his family and toward a shimmering light.

“As I drew closer, the light took on the shape of a woman clothed in a luminous robe hovering above me…Words that I will never forget came next: ‘Michael, it is not your time. You must to go back. There is much to do.’”

Rebuilding from the ground up at Spaulding

There was indeed, “much to do,” Hession learned during his lengthy recovery, which began at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital.

“When I arrived at Spaulding, I couldn’t move any extremity,” Hession recalled. “I couldn’t even swallow.”

Muscle atrophy from his time intubated in the hospital, along with Guillain Barre Syndrome, a viral illness that caused transient paralysis from the neck down, meant Hession would have to rebuild from the ground up.

“I tell everyone, that South Shore Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital saved my life and Spaulding gave me my mobility back.”

Recovery was a slow process.

“I was totally dependent on other people helping me with everything,” he said. “Little by little, they rebuilt me.”

Well-trained, patient and kind, the Spaulding staff was incredibly positive and knew how to motivate patients and give them hope, Hession said.

Colleen recounted how one physical therapist motivated Michael by incorporating ballroom dancing into his exercises.

In addition regaining his physical strength, Hession also needed to recover from the mental and emotional impacts of surviving a critical medical illness.

The same post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms that face military personnel returning from deployment, can affect patients recovering from a critical illness, Hession said.

Acknowledging he had PTSD and working through it with cognitive behavioral therapy, allowed Hession to get past the anxiety, nightmares and insomnia he experienced in the aftermath of his illness.

“When you go through a critical illness like this, you don’t go back to where you were. You find a new normal,” he said. “The people who are able to rebuild their lives are those who look to the future and find meaning, purpose and happiness again.”

Lessons learned and key takeaways for healthcare providers

Hession said his recovery has not been a straight line. Since his ordeal with ARDS, he has faced several other serious illnesses including diverticulitis, two major abdominal surgeries and cancer.

Through all of these health challenges, Hession has leaned on the lessons he learned as a critically ill patient to become a better physician.

After hearing about his experience, Smith, now President and CEO of South Shore Health, urged Hession to write a book that could inspire and inform anyone caring for critically ill patients.

Hession describes “Physician Heal Thyself” as part memoire, and part self-help guide for patients and families experiencing critical medical illness.

“More importantly,” he said, “it’s a book to help other healthcare providers become better at what they do.”

“Compassion and empathy are the true superpowers every healthcare provider needs to master,” Hession told the Schwartz Rounds crowd.

Another takeaway for providers relates to the care of comatose or intubated and sedated patients.

“You must always have as your base case, that your patient can hear you, has awareness and is utterly terrified by what is happening to him,” he said.

“No matter how busy you are, take the 60 seconds to speak to your patients with compassion and empathy. It’s your superpower and something that no one else in that moment can do.”

Cardiologist Michael Hession, MD, FACC, FACP served as Chief Medical Officer at Brigham Health Harbor Medical, is a member of the South Shore Health medical staff, an attending physician at South Shore Hospital and a consulting physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Hession’s book, “Physician Heal Thyself” is available at Amazon.com and BarnesandNoble.com

Author

South Shore Health